Open Door Policy, the new album by the reclusive DIY pop-rock experimenter Alexei Shishkin, is out on June 28th.

Influenced by such underground luminaries as Doug Martsch, Dean Wareham and home-recording godfather R. Stevie Moore, the album is a wonderfully rustic coagulation of these disparate elements, all presented through Shiskin’s idiosyncratic lense. These sources of revery can be heard in the music’s stylistic preoccupations, occasionally ramshackle aural collages and laid-back, dry delivery, the latter clearly in thrall to the master of the wry aphorism, David Berman, in the songs’ artful yet heartfelt observations.

Open Door Policy is a varied but highly enticing stew of old sounds given new meaning. Album opener The Drummer kicks things off beautifully, all slacker acoustic guitar and nonchalant drumming with wonky warbling keys sounding like an abandoned ice cream truck escaped from an early 90s video game. Third single, Rose Gold, feels like a stoned incarnation of mid 70s pop-rock, all strutting blues guitar and funky rhythm, whose louche bass, lounge swagger and bad shirt aesthetics coalesce in their own seductive way. There’s a hazy, Strokesy swagger to the Velvets strut and twangy guitar lines found throughout these songs, the droll delivery clearly indebted to Berman but with a dream-pop haze all of its own.

The saxophone that keeps cropping up unexpectedly skirts animatedly above the densely frothing mix with Bowie-esque abandon. It goes full ‘after-dinner pop jazz ‘ at times which should feel jarring but somehow just adds to the bizarre, late-night urban ambience. Covid in G concludes proceedings at a more sedate pace but is equally lovely for this subtle tonal shift- all serene paradiso atmospheres and soporific slide guitar that is reminiscent of M Ward’s early instrumental experiments.

There are echoes too of Stephen Malkmus in Shishkin’s delivery and the occasional bursts of ragged fuzzed-up electric guitar Some tracks occasionally feel like they are hunting for a melody but still summon up enough rough-edged potency in their dynamics to grab the attention. Mostly though there a hooks a plenty and in the lo-fi, lackadaisical production, there is a decidedly New York cool to proceedings.

Musical touchstones and reference points are suitably esoteric therefore- the ramshackle delivery almost echoing Mayo Thompson at times- as heard on Ruby where a country twang and southern slide clings to the song’s edges. Above all though, it is the far-reaching, ever-present spectre of The Velvets that looms with greatest prevalence, and it is a ghost that haunts the album’s heart most happily.

Open Door Policy is a wonderful collection of songs by a curious and engaging talent who deserves to be more widely known. Released on Candlepin Records at the end of June, I would certainly recommend picking up a copy.

M.A Welsh: You’ve said that you will not be taking to the stage any time soon; I can understand this mindset as we’ve been recording and releasing music for over 20 years and have never played live. Do you enjoy the possibilities of live performance in other artists though? If so, what is the most eye-opening/life-changing/inspirational show you’ve been to and what made it so significant for you?

Alexei Shishkin: When it comes to live performances from other artists, I always appreciate them, but at this point, I rarely attend. Instead, I’ll try to support by buying merch and tapes from bands I like.

When I was younger, I voraciously devoured each and every live music experience: dank basements, dingy bars, cramped DIY spaces, etc — I even created and hosted a short-lived YouTube series when I lived in Portland, OR, where we featured local bands playing live and then I interviewed them. Each of those moments was eye-opening in its own way, and they’ve all coagulated together to form a great appreciation for the grind that goes into playing live and touring. I’ve even made a documentary about it, so trust me, the devotion it takes to perform is not lost on me.

The most recent standout for me was last year’s Halloween covers show at the Knockdown Center. Specifically, I loved watching 95 Bulls play their Devo cover set, but in general it was amazing to see the variety of acts, and it was a nice reminder of just how much art and music is being made locally.

M.A: Richard Dawson (the British songwriter rather than the American TV host) mentioned once about the importance of mistakes in music; he spoke of a song full of faults being rich in fault-lines where great things can be both torn apart and brought together and where new life is born. In your own approach to music, you speak of embracing the rough edges, that perfect imperfection; why is this important to you?

A: I agree with that idea about the importance of mistakes. I don’t necessarily think the “rough edges” in my music are driven by mistakes, but that they’re more rooted in a “first thought, best thought” mindset.

Personally, I value spontaneity and improvisation in the creative process more than rumination and careful calculation. Not to say it’s not important to plan and consider your art, but in my opinion (and this is just my process) it’s easier to improvise and refine from there, instead of trying to figure every step out in advance. Can’t stress enough though: there is no right answer. Just make something!

M.A: You have said that R. Stevie Moore is someone you admire; I wondered, is his a sonic influence or more his mindset/approach to the creative process that has inspired you?

A: While I love his music, the influence on me is 90% due to his approach. He’s an incredibly talented musician, more talented than I’ll ever be because frankly, I don’t care to commit so much time to practicing, and I’ve had computers available to correct my mistakes since day one.

The most inspiring things about R. Stevie Moore’s work to me in a few words: variety, consistency, volume, flexibility, individualism.

M.A: C. Bukowski once said, “The crowd is the gathering place of the weakest; true creation is a solitary act.” I’m not sure I believe that wholly. What do you think? What’s the primary motivation for your own more reclusive approach to song craft?

A: Hmmm, I don’t think I agree with him fully either. I think I get where he’s coming from, and I agree more with the second half of his statement, but saying “the crowd” is where “the weakest” gather is maybe a bit much.

I don’t necessarily find my approach “reclusive” to be honest — I think it’s more utilitarian than anything. I started making music by myself because I had a computer and some thrift store instrument finds, but I didn’t know anyone who played music. Over time, I’ve stuck with that process, mostly because the more people you get involved (in any social activity, really), the harder it is to corral everyone, schedule things, etc.

And ultimately, solo home-recording is cheaper. Every so often (like on Open Door Policy), I’ll treat myself to a more traditional studio experience with friends playing on the album, and it’s an amazing experience, but like I said, it’s just that: a treat. The friends who play are kind enough to waive any session fees, so in return I do my best to cover expenses (food, housing, transport, etc), and then there’s studio fees, engineering, mixing, mastering to pay for. You know the drill, this isn’t anything special, all bands have to pay for these things.

The flip-side of it is, I can make an album like dagger, from 0% to 100% in like a week at my apartment. Over the years I’ve compiled a bunch of different styles of drums from places like Drum Drops and The Drum Broker (I’m actually thinking about getting the Super Dead Drums from Jake Reed soon as well, those sound amazing). I have a bass guitar, a digital piano, an electric guitar, a synthesizer, and a nylon-string acoustic at my house. I have three weirdo microphones. I have Garageband. Basically I wrote, recorded, mixed all of that in like 5 days, and then sent it to a friend to master. Obviously, that process costs less than a traditional process.

And at the end of the day, both dagger and Open Door Policy are perfectly valuable and valid in their own ways — some people will like one more, some will like the other, some will like both, some will like neither. Regardless, I write music for myself.

M.A: Although you have professed a desire to create away from the stage lights, the new album is rich in collaboration. How has working with this varied cast of characters enriched your approach to the songs?

A: Yes, this has definitely been my most collaborative album to date. The approach was much more bare bones than usual (from my end, at least). If it’s just me, or maybe me and one other person, naturally there’s more on my plate. In the case of Open Door Policy, I was able to basically just come up with the chord progressions and then go into the studio, where everyone else figured out their parts. Again, it was very “first thought, best thought” — by which I mean: I wasn’t very precious about it. Once the musicians had parts they liked, I also was satisfied most of the time, which is why it’s always a blessing to play with talented musicians.

“Rose Gold” is probably the track that sums up this new approach the best. My usual love of improvisation is present in the lyrics — they were mostly made up on the spot and were slightly different in each take. On drums, Ian Dwy came up with some great parts, Dave Kahn was given free reign on bass, Eyal Sala played woodwinds, and Bill Waters played the lead guitar parts that basically keep the song flowing. While we tried our best to lay the thing down live, we were blessed to have the genius Bradford Krieger (Big Nice Studio in Lincoln, RI) punch and comp parts as needed to bring it all together.

M.A: I love the use of saxophone on the album – it works so perfectly and so surprisingly at times; were you playing with expectations by deploying it so vibrantly at moments on this record or did it just feel right?

A: I also loved the sax on it. Sax was by Ivan Rodriguez, recorded remotely in Argentina. He also played on my 2023 album Goodbye Sunrise. He was an absolute pleasure to work with. I basically sent him songs that were mostly done, and I either left him spaces to solo (where he would send me a few versions and we’d usually comp them together) or I would ask him to double certain melodies or play harmonies. But at the end of the day, I gave him freedom and let him do his thing because he’s a very talented player.

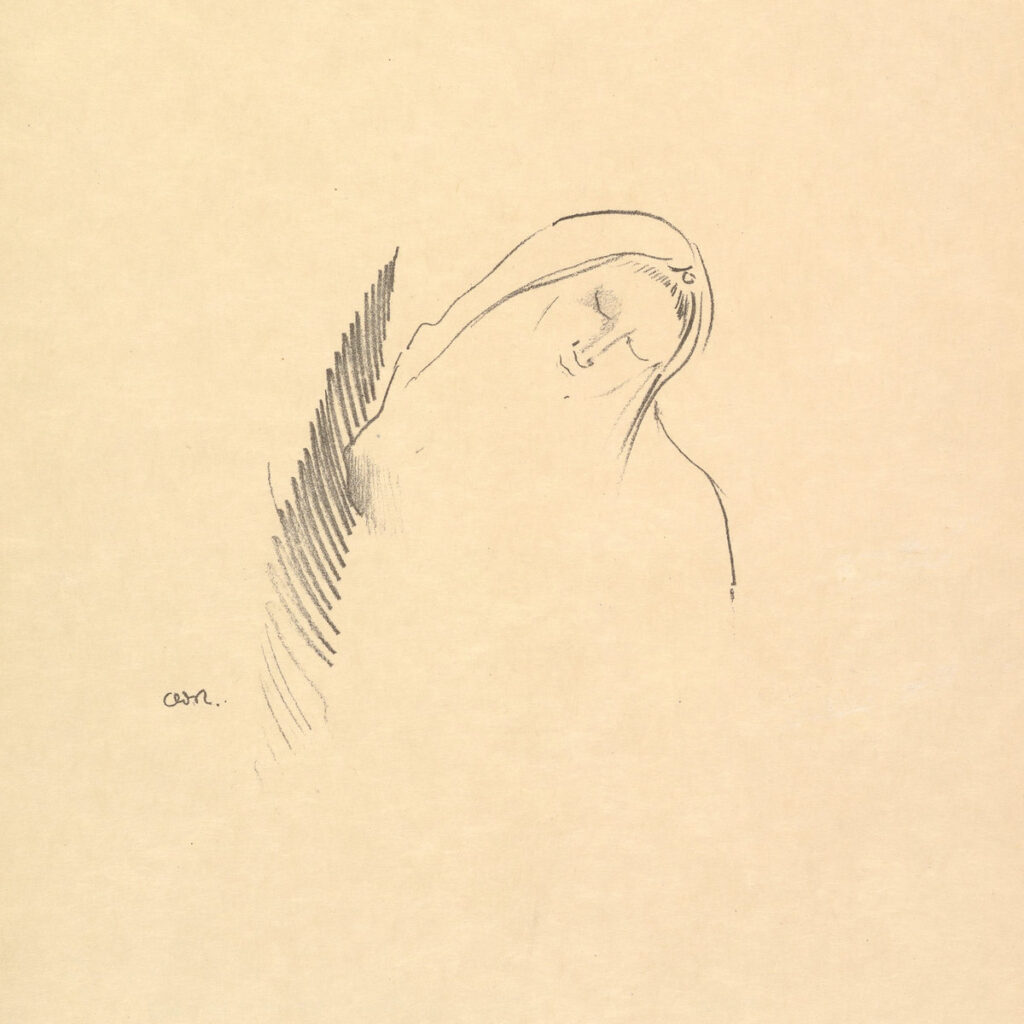

M.A: I love the simplicity of the cover art, “Sleep” by Odilon Redon (1898). What was it about this image that you felt captured the music’s intent?

A: Thank you! I liked the art, too. There was something effortless about the drawing which I liked; it felt rough, candid, impressionistic. Also, in a bizarre stroke of coincidence, I’m actually doing a very similar pose in the press photo for this album (shot by Ragan Ivy Mueller).

It’s from The Met’s Open Accesscollection. In a nutshell, that collection is a public-domain, Creative Commons Zero-licensed database of select works that are available for unrestricted use. I spent an hour or so browsing through there and pulling pieces I liked, and then I designed ~25 different album covers. I sent those versions to esteemed art historian Graham W. Bell for feedback, and then I think I ended up picking a piece that he didn’t even recommend (sorry, Graham!).

If you buy the Open Door Policy cassette tape, the J-Card has some alternate art options on the inside that you can check out.

M.A: It feels like an album that reflects a city atmosphere but there are also sounds that could have drifted in from the country. Was it a conscious choice to toy with these dichotomous sound worlds?

A: Interesting — I didn’t consciously try to do any city vs country dynamic, but I see where you’re coming from. I’ve always thought about this collection of tunes as cold vs warm. I think the front half of the album sounds warmer (more “country” maybe), and the back half of the album sounds colder (more “city”), before resolving with one warm track.

The “country” idea might also be informed by the lap steel (played by Bradford Krieger). I think that features pretty heavily throughout, but especially on “Ruby” and “Covid in G”. And you know what, now that I think about it, I wrote “Ruby” the day Kenny Rogers died (ergo, me ripping off the song title), so that’s got a bit of a country thing to it.

Yeah, who the hell knows — good catch, though, I’m glad you picked up on a cool pattern! At the end of the day, that’s my goal: to make the art I want to experience, and then see what other people find in it.

Written by M.A Welsh (Misophone)

1 thought on “Album premiere: Alexei Shishkin – Open Door Policy + interview”

Comments are closed.